Submarine

Junsung Kim

'Submarine'

Development of a Control and Image Acquisition System for a Small-scale AUV

This study presents the design and implementation of a low

cost small-scale underwater vehicle that integrates depth

control and video recording capabilities using open-source

hardware. The vehicle employs an acrylic pressure hull

sealed with O-rings, a magnetic coupling propulsion sys

tem, and a syringe-based ballast for buoyancy adjustment.

A pressure sensor and PID controller are used for depth

stabilization, while a Raspberry Pi camera module enables

onboard video capture. Experimental results in a small tank

demonstrate stable waterproofing, reliable propulsion, and

effective PID-based depth control. These preliminary re

sults suggest that autonomous underwater control can be

achieved using low-cost hardware. This midterm report

summarizes progress up to functional verification in a small

tank environment and discusses the ongoing development

toward improved mechanical stability and control perfor

mance.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

In recent years, the use of autonomous underwater vehicles

(AUVs) and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) has been

rapidly expanding in various fields such as marine resource

exploration, water quality monitoring, and underwater res

cue operations. These underwater robotic systems are ca

pable of performing diverse tasks including depth mainte

nance, attitude control, and video data collection, which

make them highly valuable for both research and indus

trial applications. However, commercial AUV/ROV sys

tems typically require expensive sensors, precise control

units, and waterproof housings, resulting in high design

complexity and maintenance costs. As a result, they are of

ten inaccessible for educational or experimental purposes.

To address this limitation, there has been growing inter

est in developing small-scale underwater robot platforms

using low-cost components. With the widespread avail

ability of open-source single-board computers (SBCs) such

as Raspberry Pi and Arduino, as well as affordable IMUs,

pressure sensors, and camera modules, students and re

searchers can now implement basic underwater control sys

tems at a relatively low cost. This DIY (Do-It-Yourself) ap

proach provides significant educational value by allowing

learners to experience both hardware design and control al

gorithm implementation in an integrated way. Furthermore,

such systems can be extended beyond simple manual con

trol to autonomous operations and data acquisition, serving

as versatile experimental platforms.

Existing DIY submarine projects tend to show that as

the project scale and budget increase, the system is func

tionality improves; conversely, with lower budgets, the de

sign often becomes simpler and the control capability more

limited. Consequently, most small DIY submarines are re

stricted to basic propulsion control based on manual opera

tion, and there are relatively few examples of low-cost sys

tems that successfully integrate stable depth control with

video capture functionality. Therefore, developing a small

prototype submarine that combines depth maintenance us

ing a PID control system with an onboard video recording

module?built entirely from low-cost, open-source hard

ware?represents a meaningful engineering challenge at the

undergraduate level.

1.2. Objectives

The primary objective of this study is to design and build

a small underwater vehicle prototype that integrates depth

control and video recording functions using low-cost RC

components and open-source hardware. This interim report

focuses on the design process and preliminary experimental

results, based on the following specific goals:

1. Hardware System Design and Integration: Fabricate

the main body of the submarine using 3D-printed parts and

RC components, integrate key modules such as thrusters,

microcontroller (MCU), pressure sensor, and camera, and

verify waterproofing and communication stability. 2. Im

plementation of Depth Control System: Develop and test

a PID control algorithm that maintains a target depth us

ing pressure sensor feedback. 3. Video Recording Func

tionality: Mount a compact camera module to capture and

store underwater footage, and verify normal operation by

checking for frame drops and visual clarity during under

water tests.

The scope of this midterm report is limited to the first

design and prototyping phase, and to functional verification

in a small water tank environment. Performance evaluation

focuses on static depth control in shallow water.

In future work, the system could be extended to include

performance testing in more dynamic environments, as well

as the integration of sonar-based depth sensors for more ac

curate measurement and partial autonomous control. How

ever, waterproofing challenges and cost constraints of un

derwater sensors remain important considerations for future

implementation.

This project also aims to integrate key aspects of elec

trical and electronic engineering?real-time control, em

bedded sensing, and data acquisition?into a unified un

derwater application using a low-power embedded system,

thereby demonstrating practical application of multidisci

plinary engineering principles at the undergraduate level.

1.3. Organization of the Report

This report is organized as follows. Chapter 2 reviews re

lated studies and existing DIY submarine projects. Chap

ter 3 presents the hardware and software architecture of the

designed system. Chapter 4 describes experimental results

for depth control and video recording. Finally, Chapter 5

concludes the study and discusses current limitations and

potential improvements.

2. Related work

Recent developments in small-scale underwater vehicle re

search have shown increasing interest in low-cost and DIY

(Do-It-Yourself) approaches using open-source hardware

and consumer-grade components. These efforts aim to

reduce the high cost and complexity of traditional au

tonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) or remotely oper

ated vehicles (ROVs), which typically require expensive

waterproof housings, precision sensors, and professional

control systems. In particular, several hobbyist and edu

cational projects have demonstrated the feasibility of con

structing functional small underwater vehicles using plat

forms such as Arduino or Raspberry Pi, combined with af

fordable actuators and sensors.

In parallel with these grassroots developments, aca

demic efforts have also explored cost-efficient aquatic plat

forms. Ryu [4] developed a low-cost open-source un

manned surface vehicle for real-time water-quality mon

itoring, demonstrating that consumer hardware can re

liably support closed-loop control and data acquisition

in aquatic environments. Similarly, Li et al. [3] pre

sented an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) design

integrating multiple thrusters and depth control using a

microcontroller-based architecture. These studies illustrate

that both research-grade and DIY-oriented approaches are

converging toward compact, modular, and accessible under

water systems.

Numerous DIY submarine projects shared on online

blogs and YouTube channels have provided valuable ref

erences for low-cost underwater vehicle design. However,

manyofthese projects employ large-scale structures?often

exceeding one meter in length?and high-power propul

sion units, making them less suitable for small indoor

test environments or for applications with strict cost and

size constraints. Furthermore, most existing hobbyist sub

marines rely primarily on manual control via RC transmit

ters, with limited attempts to implement feedback-based or

autonomous depth control.

Among the publicly available works, the Brick Experi

ment Channel is LEGO-based DIY submarine series offered

the most systematic and instructive example [1, 2]. Through

multiple iterations, the creator experimentally implemented

buoyancy control, pressure sensor feedback, and PID-based

depth stabilization. Despite its use of LEGO parts, the

project effectively demonstrated stable underwater motion

through careful hardware sealing, sensor integration, and

control tuning. This series highlighted practical challenges

in underwater system design, including waterproofing, bal

last adjustment, and controller gain optimization.

Building upon such prior efforts, the present study fol

lows the general control framework demonstrated by the

Brick Experiment Channel (BEC), which also utilized a

Raspberry Pi-based control system for implementing PID

based depth stabilization. However, while BEC is work pri

marily focused on achieving depth control using LEGO

components, the present study extends the concept by inte

grating an onboard camera module for simultaneous video

recording. In addition, while the overall scope is compa

rable, the present prototype places more emphasis on ac

cessibility and reproducibility, employing general-purpose

materials such as lead pellets for ballast and PTFE tape for

magnetic coupling. This configuration aims to demonstrate

that stable underwater control and imaging functions can be

realized within modest resource constraints. Furthermore,

by departing from the mechanical and modular limitations

of LEGO parts, this prototype explores a broader range of

hardware configurations and sensing options. These exten

sions are expected to provide a flexible platform for sub

sequent experimentation, such as incorporating additional

sensors or utilizing the captured imagery for control and

analysis in future stages of the research.

This approach demonstrates how a low-cost, small-scale

platform can achieve both control stability and real-time vi

sual monitoring, offering potential as an educational or ex

perimental testbed for underwater control research.

3. Method

This section describes the design, construction, and im plementation process of the small-scale underwater vehi cle system. The project was divided into two main stages: hardware development and software control implementa tion. Each stage considered essential engineering aspects such as waterproofing, buoyancy and weight balance, power management, and sensor-based depth control. The over all hardware configuration block diagram of the developed AUVsystem is shown in Figure 1.

3.1. Hardware Design and Implementation

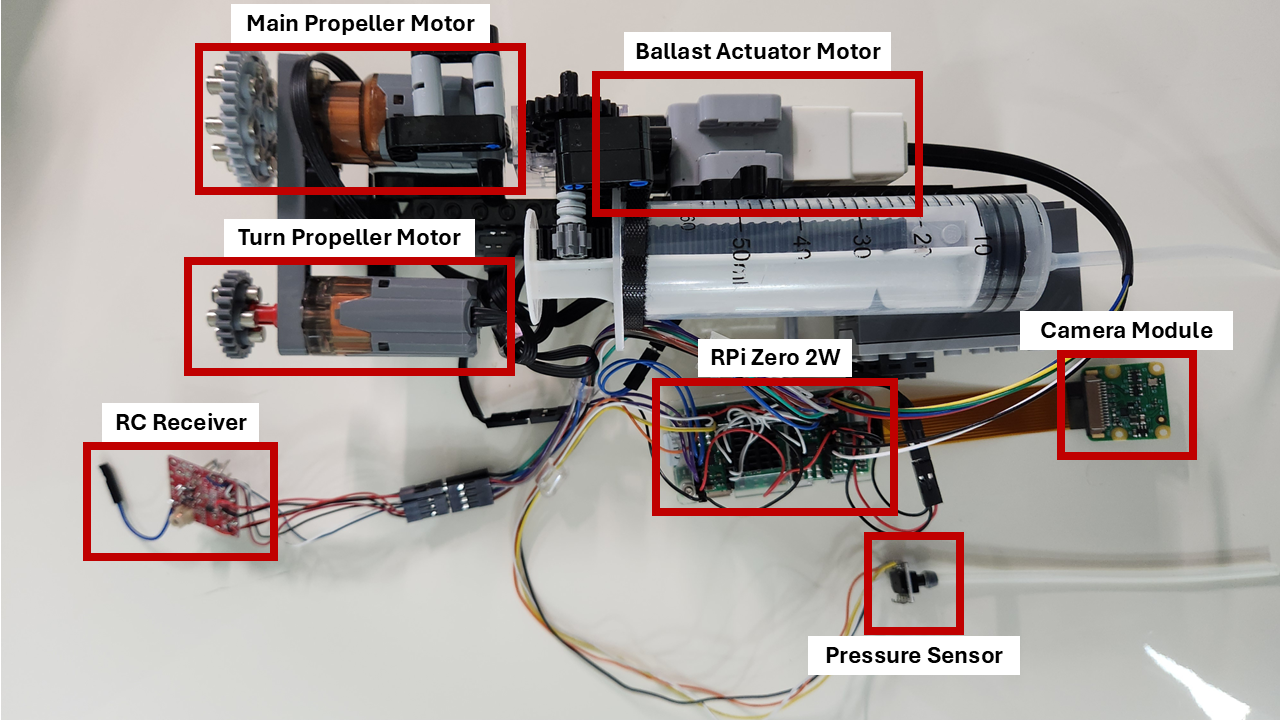

The overall external layout and mechanical configura tion of the submarine are illustrated in Figure 2, and the key components and their specifications are summarized in Table 1, which lists the major hardware components and specifications.

(1) Hull Structure and Waterproofing Design

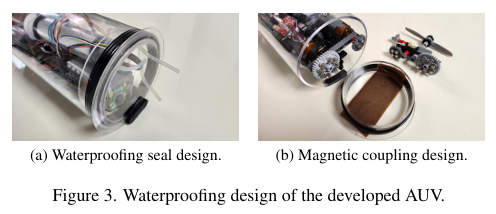

Waterproofing is one of the most critical challenges in low cost DIY submarine construction. To ensure transparency, ease of fabrication, and sufficient signal transmission for RCcommunication, an acrylic pressure hull was selected as the main body material. Acrylic allows internal inspection during experiments and provides relatively low attenuation for radio signals compared to metal housings. For hull sealing, an O-ring?based closure mechanism was adopted to achieve a balance between maintainability and watertight performance. NBR O-rings with Shore hardness 70 and 90 were used in combination, with silicone grease applied to reduce friction and improve sealing efficiency. In addition, a magnetic coupling propulsion system was imple mented using neodymium magnets to transmit torque from the internal motor to the external propeller without requir ing a physical shaft penetration, thereby minimizing poten tial leakage paths. The key waterproof sealing and magnetic coupling mechanisms are shown in Figure 3.

(2) Buoyancy and Weight Adjustment

Stable underwater motion requires precise control of buoy ancy and the center of gravity. The internal weight distribu tion was adjusted using lead pellets sealed in LDPE double zipper bags, forming a modular weight system that could be easily repositioned. A simple mechanical ballast system was designed using a syringe cylinder and a silicone tube to control buoy ancy. The ballast operates by drawing in or expelling water through differential pressure between the inside and outside of the hull, enabling fine buoyancy adjustments. The tube was routed through a small port in the front cap and sealed to prevent leakage.

(3) Heat Dissipation and Power Management

Because the interior of the submarine is tightly sealed, in ternal heat accumulation directly affects system stability. To mitigate this, unnecessary software processes were dis abled, and control loops were optimized for power effi ciency. For the power source, a LEGOLi-Pobatterymodule (7.4 V, 1100 mAh) was adopted, chosen for its safety, com pact size, and ease of recharging. Compared with 18650 Li-ion cells or standard LiPo packs, the LEGO module pro vided higher spatial efficiency and simpler integration with existing RC components, making it well suited for small scale tank experiments.

3.2. Software Design and Control Algorithm

The internal placement of electronic components, wiring, and ballast actuator inside the hull is depicted in Figure 4.

(1) Sensor Control

To measure depth, various sensing methods were evaluated. LiDAR was excluded due to light attenuation in water, and ultrasonic sensors (SONAR) were avoided because of cost and waterproofing challenges. Instead, an absolute pressure sensor (SSCMANV030PA2A3) was employed to measure hydrostatic pressure and convert it into depth readings. The sensor was interfaced via the Raspberry Pi is I2C port, pro viding centimeter-level resolution suitable for small-tank testing. The acquired data were used as feedback inputs for the PID control system.

(2) Motor and PID Control

The ballast syringe actuator was driven by a servo motor controlled through a PID (Propor tional?Integral?Derivative) loop. The control algorithm compared the measured depth with a target depth value and adjusted the motor speed accordingly. In addition, the system included separate thrusters for for ward propulsion and turning. A commercial low-frequency RC receiver module was integrated to allow manual con trol during testing, with seamless switching between au tonomous PID control and manual RC operation.

(3) Video Capture and Recording

For image acquisition, a Raspberry Pi Camera Module V2 was mounted inside the hull. The camera provided a good balance between image quality, size, and power consump tion. Video recording was implemented in Python using the picamera library, which handled frame capture asyn chronously while the main control loop continued depth regulation and logging tasks. This allowed simultaneous depth control and video capture, enabling visual verifica tion of underwater operation.

3.3. Summary

The overall system design emphasized low-cost fabrication, compactness, and stable control performance. Both hard ware and software were developed with an integrated ap proach considering waterproofing, heat dissipation, power efficiency, and signal interference. The prototype was tested in a plastic tank with a capacity of approximately 43 L (internal dimensions ? 530 * 375 * 275 mm) to verify basic diving, surfacing, and video recording capabilities. These results demonstrate the feasibility of constructing a low-cost, open-source underwater vehicle platform that can serve as a foundation for future expansion and advanced control experiments.

4. Experiments

This chapter describes the experimental procedures con ducted to evaluate the performance of the developed small scale underwater vehicle. The experiments were divided into two main categories: (1) hardware performance tests and (2) control and vision system tests. All experiments were performed in a small indoor water tank to verify wa terproofing, propulsion, depth control stability, and video recording functionality.

4.1. Hardware Performance Tests

(1) Waterproof Performance Test

Waterproof integrity is a key aspect of the vehicle design. Initially, custom O-rings were fabricated by manually cut ting and bonding rubber strips, as commercially available ones of the required size were unavailable. These handmade O-rings maintained watertightness for short durations (ap proximately 10 minutes), but gradual leakage was observed over several hours. To address this issue, commercially produced NBR (nitrile rubber) O-rings were selected and tested. The standard ized O-rings successfully maintained waterproofing for sev eral hours without leakage. However, when using single material O-rings, friction during opening and closing of the hull caused displacement and handling inconvenience. To improve sealing reliability, a combination of O-rings with different hardness levels (70 and 90 Shore A) was adopted, along with the application of silicone grease. This configuration enhanced both sealing stability and ease of maintenance. Additionally, it was observed that the inner diameter of the silicone hose connecting to the syringe bal last significantly affected leakage resistance. After testing three hose sizes, a thicker hose was selected for final imple mentation. The current waterproofing design has demonstrated stable operation during long-term tests. Future improvements in clude refining the O-ring groove structure to optimize me chanical fit and sealing performance, balancing precision machining requirements with durability.

(2) Propulsion and Magnetic Coupling Tests

The propulsion system consists of a main propeller and a turning propeller, both driven via a magnetic coupling mechanism. To minimize frictional wear and magnetic slip page, PTFE (Teflon) tape and silicone spray were applied to the coupling interface. Without lubrication, noticeable tape abrasion occurred due to friction, but this was significantly reduced after lubrication. Experimental trials in the small tank showed that the main propeller provided stable forward and backward motion, while the turning propeller responded reliably to lateral con trol commands. Quantitative measurements such as thrust magnitude and turning radius could not be obtained due to the tank is limited size. In future work, experiments in a larger water tank will be conducted to characterize propul sion performance more precisely. The use of UHMW(ultra high-molecular-weight) polymer tape is also being consid ered as an alternative coupling material to enhance wear re sistance.

4.2. Control and Vision System Tests

(1) Manual RC Control and PID depth control

Control performance was tested in a transparent acrylic wa ter tank. In manual RC mode, the low-frequency radio sig nal operated stably above the water surface but experienced signal attenuation when transmitted through the tank walls. This was attributed to the acrylic thickness and inherent un derwater signal loss, suggesting the need for future tests in a larger environment.

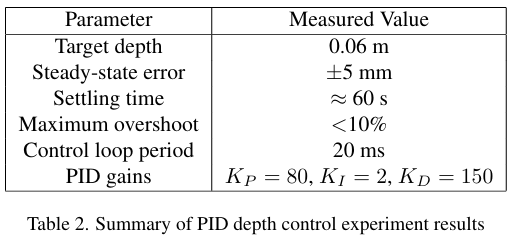

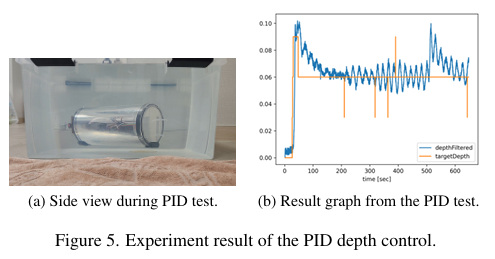

The PID depth control mode was activated through a spe cific button combination on the RC transmitter. Once sub merged, the system maintained stable buoyancy and depth near the target value. The PID controller was tuned em pirically with proportional, integral, and derivative gains of KP=80, KI=2, and KD=150, respectively. Initially, KP was increased to speed up the depth response, and then KD was adjusted to reduce overshoot. Finally, a small KI value was introduced to eliminate steady-state error while maintaining stability. Figure 5(b) shows the measured fil tered depth (depthFiltered) and target depth (targetDepth) over time during a step-response test. A summary of the quantitative performance metrics obtained from this exper iment is provided in Table 2. When the target depth was increased from 0 m to approximately 0.06 m, the vehicle reached steady-state within ? 60 s, with a maximum over shoot of less than 10% and steady oscillations below plusminus 5 mm after settling. The slight oscillation seen after 400 s is attributed to mechanical backlash in the syringe gearbox (? 0.5 ml deadband), as defined in the control parameters. The average control loop period measured from logs was ? 20 ms, confirming real-time operation of the PID loop on the Raspberry Pi Zero 2W. However, during prolonged operation, mechanical loosening occurred at the connection between the syringe ballast and motor assembly. To address this, the ballast was secured using Velcro ties, and reinforce ment of the gear mount and 3D-printed housing is under consideration.

Wheninitiating PID control at the water surface, a short de lay in depth response was observed, likely due to surface tension effects and buoyancy transitions at the air?water in terface. Additionally, due to the limited tank size (length ? 530 mm, depth ? 275 mm, capacity ? 43 L), it was not possible to quantitatively evaluate steady-state or dynamic performance indicators such as linear acceleration or turn ing radius. Furthermore, the wall effect caused by the nar row tank may have influenced the hydrodynamic response, implying that the PID gain values tuned in this setup could differ from those optimal for open-water conditions. Fu ture work will focus onrefining the initial control conditions or applying a gradual mode transition to improve response smoothness.

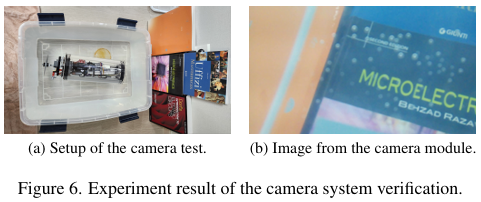

(2) Camera System Verification

Figure 6(a) shows the experimental setup for underwater video recording, and Figure 6(b) presents a sample im age captured by the onboard camera during the test. The camera system utilized a Raspberry Pi Camera V2 mod ule for underwater video acquisition. The recording pro cess was executed concurrently with control operations via Python scripts, confirming stable simultaneous operation. The recorded footage exhibited no significant degradation in image quality due to lighting or reflection in the tank en vironment. The Pi Camera V2 was operated at 720p and 30 fps, providing a reasonable balance between underwa ter image clarity and SD card storage capacity. At this set ting, a ten-minute recording occupied approximately 220 MB, which was verified to be suitable for continuous test ing sessions without data loss. The video was stored on an onboard SDcard, and slight frame vibrations were observed corresponding to propeller movement and buoyancy adjust ments. These results indicate the potential for implement ing post-processing techniques such as digital stabilization to enhance video quality.

4.3. Summary of Results

The experimental results confirmed that the developed small-scale submarine achieved stable waterproofing, re liable propulsion, effective depth control, and functional video recording. In particular, the PID-based depth con trol demonstrated that autonomous underwater stability can be achieved using low-cost open-source hardware. Nevertheless, limitations remain in testing environment size, mechanical robustness of the ballast actuator, and RC communication range. Future work will focus on improving these aspects and extending experiments to larger tanks or open-water conditions to validate system scalability.

5. Conclusion

This study presented the design and implementation of a small-scale underwater vehicle prototype that integrates depth control and video recording functions based on low cost, open-source hardware. The system employed an acrylic pressure hull with O-ring sealing for waterproofing, a magnetic coupling propulsion system for power transmis sion, and a syringe-based ballast mechanism for buoyancy adjustment. A compact battery module was also incorpo rated to enhance power and spatial efficiency within the sealed hull.

On the software side, a PID-based depth control algo rithm was implemented using pressure sensor feedback, al lowing the vehicle to maintain target depth automatically. The RC transmitter enabled manual and automatic mode switching, and experimental tests in a small water tank con f irmed stable operation of both the depth control and video recording functions. Although the experiments were con ducted in a limited environment for a short duration, the results demonstrated that autonomous underwater control can be achieved even with low-cost components and sim ple open-source tools.

Several limitations remain. The confined test environ ment made it difficult to verify long-term stability and op timize PID gain parameters. Mechanical wear and minor leakage were observed around the ballast?motor coupling, indicating the need for structural reinforcement. RC com munication suffered from signal attenuation due to the water tank is electromagnetic characteristics, suggesting that fur ther testing in larger or open-water environments will be necessary. In addition, the current vision system is limited to video recording only, without real-time transmission or image stabilization.

Future work will focus primarily on improving system stability and robustness through extended testing and me chanical refinements. Additional enhancements are being considered as longer-term possibilities rather than immedi ate goals:

(1) Mechanical Design Improvement: Reinforce the cou pling housing and propeller mount by reprinting them with more durable 3D printing materials such as ABS or PETG, which offer improved mechanical strength and heat resis tance compared to standard PLA.

(2) PID Control Refinement: Continue empirical tuning and stability tests in larger environments, and explore sim ple adaptive or gain-scheduling strategies for improved con trol performance.

(3) Vision System Exploration: Investigate the feasibility of wireless or Wi-Fi-based video transmission in shallow water environments, while carefully evaluating power con sumption and signal attenuation issues.

(4) Sensor Evaluation: Consider testing low-cost sonar or ultrasonic modules for distance and depth measurement if budget and feasibility permit.

In summary, this project demonstrates a practical and educational example of integrating core underwater robot functionalities?waterproofing, propulsion, depth control, and vision capture?using affordable open-source hard ware. The developed prototype provides a solid foundation for continued experimentation and incremental improve ment toward more stable, reliable, and versatile small-scale underwater systems. Overall, the results also confirm that stable underwater control and onboard video acquisition can be achieved without relying on high-cost commercial sys tems, highlighting the educational and engineering signif icance of employing open-source hardware such as Rasp berry Pi for applied mechatronics research at the undergrad uate level.